Written by Gauthier Leonard, co-founder of Suzaku

Decentralization is a spectrum. It is costly, hard to measure, and it seems like most users don’t care at all. So a legitimate question is: does it really matter? The truth is, most of the time, it doesn’t. But when it is eventually put to the test, you’d better hope your network is decentralized enough, or you might lose just about everything.

In this article, I’ll explain what risks centralized L1 networks face and what minimal requirements one should look for to minimize them.

Of course, I am a proponent of progressive decentralization (that we address with the Suzaku protocol). For the average project, it is nearly impossible to start as an L1 network distributed among many participants. But as we’ll see, the first steps toward decentralization go a long way in drastically reducing risks.

Note: This article focuses more specifically on Avalanche L1s, but the same reasoning can be extended to most L1 networks.

Hacks (too) often make the headlines in crypto. We can classify them into 2 categories: smart contract hacks and OpSec hacks.

For a long time, smart contract hacks have been the most common, and also the area where builders allocate the most budget through the famous audits. However, OpSec hacks have been on a recent streak. Just this year, 2 come to mind immediately:

As AI auditing tools strengthen the robustness of smart contracts, the primary remaining attack vector becomes OpSec exploits: infra hacks (front-end, DNS, API), social engineering attacks, and supply chain attacks.

If the biggest players in Web3 can be breached (Kiln was the biggest staking provider in crypto before being hacked), everyone is at risk: the blockchain service providers, the L1 teams, etc. Keep that in mind for the rest of the article.

Several properties come to mind when we think about what we expect from a “decentralized” L1:

But we often forget the most important: the security of user funds, and more specifically, of bridged funds. If all your users lose their funds, you can probably say goodbye to your project.

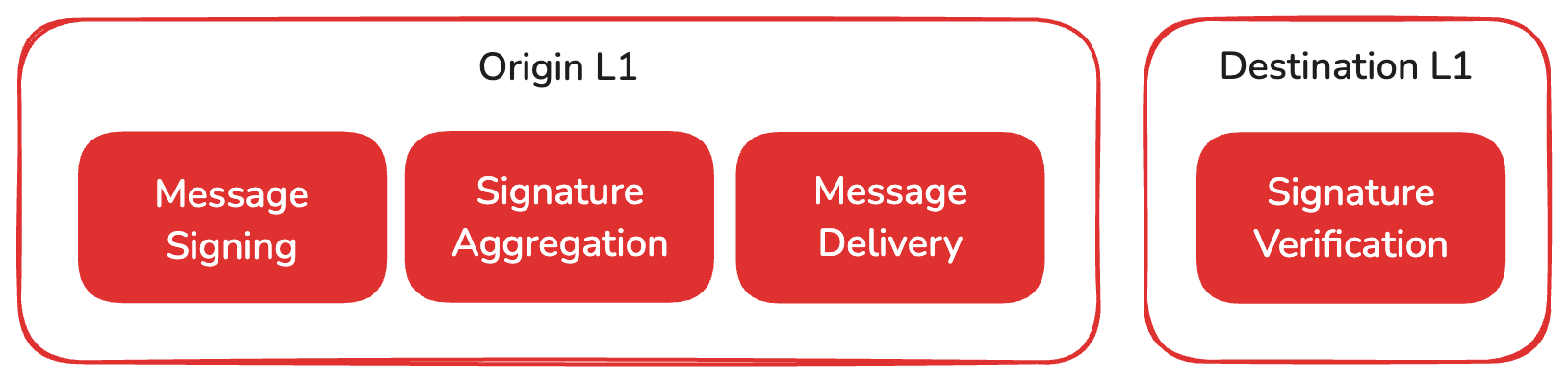

In the context of Avalanche, an L1 communicates with other chains (esp. with the C-Chain for access to liquidity and integrations) using ICM (InterChain Messaging), and pays a rent (L1 validator fee) in AVAX to the P-Chain for that.

While extremely efficient, ICM has known weaknesses, specifically for chains with a low number of validators, and more importantly, a low number of operators (= independent entities running validators).

ICM relies on BLS signatures to verify messages on destination chains, requiring a signature of at least 67% of the L1 weight to be considered valid. A typical message would be the bridging of assets back to the Avalanche C-Chain.

If an attacker gets access to BLS keys corresponding to 67+% of the total weight, they can effectively bridge all assets without any corresponding transaction on the L1 itself.

Let’s take the setup of the average L1 today:

Here, at least 2 scenarios could lead to the compromise of the 5 validator BLS keys:

Once the attacker has the BLS keys, they can bridge out all the L1 TVL back to the C-Chain.

Today, more than 80% of Avalanche L1s have less than 10 validators, and often, there is a single operating entity (see L1s stats).

Pretty simple: the more the L1 validator set is distributed between independent operators, the more resilient it is to OpSec hacks.

There is a good old metric that measures the minimum number of entities needed to collude to attack a chain: the Nakamoto coefficient.

Nakamoto coefficient > 2 = Each operator controls strictly less than 67% of the L1 total weight

Relying on a single operating entity can be acceptable during bootstrap, but L1 teams should onboard third parties ASAP to eliminate any SPOF (Single Point Of Failure). The longer you wait and the product gains traction (= TVL grows), the bigger the risk of being targeted and eventually losing it all.

Of course, the higher the Nakamoto coefficient, the more you reduce risk. And you also improve the other properties of the chain: liveness, censorship resistance, and credible neutrality.

Here, it is important to differentiate decentralization and permissionlessness.

Reaching an acceptable decentralization level doesn’t require being permissionless: onboarding 2 trustworthy partners to your chain and giving them 20% of the network weight each already eliminates the SPOF.

By the way, there is a sticky tendency in crypto for pushing permissionlessness and solo-validators (coming from the Ethereum ethos), which is in reality counterproductive for smaller networks. You’ll have to sacrifice other guarantees, esp. liveness, for the sake of pristine decentralization. But we’re moving away from the topic, so I’ll save that for another time.

When we talk about the validator set, there are the hardware operators, but there is also the selection mechanism: how are validators selected to secure the network?

On Avalanche, since the Etna (a.k.a. Avalanche9000) upgrade, an L1 validator set is managed through smart contracts (the Validator Manager contracts). A lot of different security models can be implemented: Proof of Authority, Proof of Stake, etc. Suzaku offers a way to transition from one to the other.

Like any smart contract, the security ultimately comes down to: who has admin rights? (in PoA, who can add/remove validators at will) And who has upgrade rights? (can change the security model and reshape the validator set). If both those accounts are EOAs, you’ve found yourself a SPOF again.

Critical validator set management functions must be either secured by multiple parties (multisig, governance) or immutable.

While all the risks and mitigations described above are well understood by savvy technical nerds like myself, the majority of users and L1 builders are not totally aware of them.

This is why I think that we SHOULD have proper stages for Avalanche L1s, very similar to what we can find on L2BEAT for Ethereum L2s, to (i) clearly inform users of the risks they are taking and (ii) guide L1s on the road to improving security through decentralization.

A discussion around that topic has just started on the ACP forum (on GitHub). I encourage all actors, Ava Labs, L1 builders, professional operators, and community members to participate.

Once significant progress has been made, count on me to publish a follow-up article on the matter!

Kids don’t care about decentralization, but responsible adults should.

If you’re a builder and want to dig deeper into this topic, I’m always happy to chat and help you take action. Hit me up in DM on X (@Nutymoon) or Telegram (@Nuttymoon)!